When in 2000s many of us started our university studies in the fascinating field of Geography and started building up our skills in Geographic Information Systems (GIS), one of the first things that comes up in our minds should be the notorious file format .shp commonly known as shapefile. Back then this type of file was dominant in the vector analysis of geo-data in the realm of Geo-sciences. In this article we are going to discuss about the file itself and how things have been changed in the course of two decades characterised with a revolution and deep transformation in the sphere of technology, tools and data.

What a shapefile is doing?

Shapefile is one of the most widely used formats. It is simple, efficient, and it is supported by many GIS applications, as it enables the visualization, analysis, and manipulation of geographic data. Shapefiles represent real-world geographic features like rivers, roads, cities, lakes and boundaries among others. These spatial data can be represented as vector data being stored in .shp in the form of points, lines, polygons and polylines.

Shapefiles can store also spatial coordinates, such as latitude and longitude, along with attribute data like population and land use. They support various coordinate systems and projections, allowing the representation of the Earth’s curved surface on flat maps. In GIS and spatial analysis, geographers utilize shapefiles in software like ArcGIS and QGIS to examine patterns, relationships, and trends in geographical data. These data are essential for mapping climate change effects, analyzing urban growth, and studying wildlife habitats. Additionally, shapefiles play a crucial role in cartography and map-making, being widely used in both digital and printed maps for navigation, planning, and research. They allow for the customization of maps by incorporating multiple layers, such as roads, vegetation, and elevation. In remote sensing and environmental studies, shapefiles help integrate satellite imagery with spatial data in the form of raster files (like .ecw, .geotiff, .dem etc.) for land cover classification and are valuable tools for monitoring deforestation, soil erosion, and disaster management.

The first shapefile was created way back in 1994, by ESRI. It was used with GIS software application called ArcView 2.0. which was actually the predecessor of the wide known ArcMap. ArcMap’s first version in 1998 was actually ArcView 8.0.

Shapefile’s anatomy

A shapefile is able to contain both graphics or geometries of the geographic features in the form of vector data and attributes. The latter in other words are tables or databases where the charactersitics of the geo-features are expressed as text (strings) or numbers. For example the attributes can represent population or area in the form of numbers or names, qualities and so on, in the form of text.

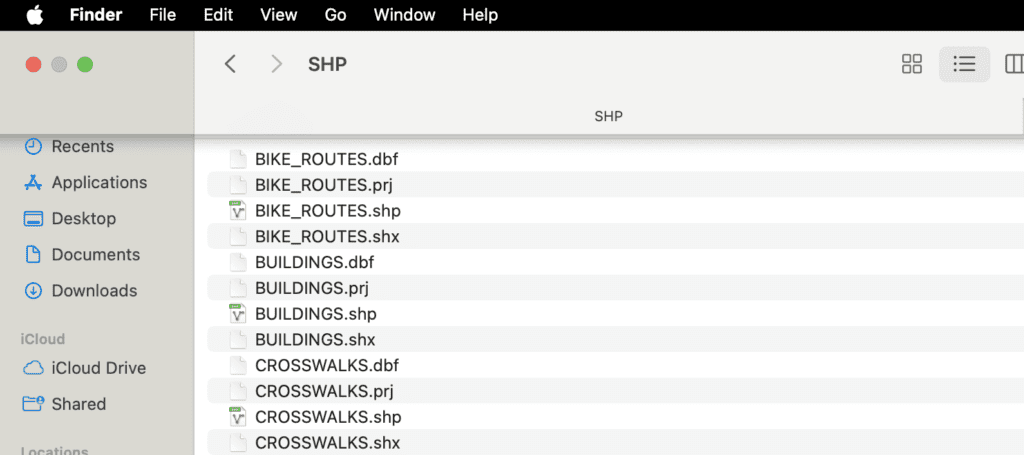

A shapefile is not a single file but a set of related files with the same name but different extensions. The essential ones are:

- .shp – Stores the geometry (shapes).

- .shx – Index file linking geometry to attribute data.

- .dbf – Stores attribute data in a tabular format (like a spreadsheet).

Other optional files include:

- .prj – Contains projection information (coordinate system).

- .cpg – Defines character encoding for text fields.

- .xml – Stores metadata about the shapefile.

Pay attention on the fact that a shapefile will not work if you just pick the .shp file. For example given the above photo, in order to get the buildings or the routes visualized you have to pick all four files (.dbf, .prj and .shx along with the .shp).

The big advantage of the shapefile almost 30 years after its debut, is that it is very portable and versatile file format. As a matter of fact it can be zipped up and quickly be emailed or shared. Even though it is developed and deployed for commercial reasons by a GIS software giant. In the retrospect its use and adoption is universal by geographers and GIS experts as it is user friendly, with low-to-no-code requirements, compatible and interoperable within various GIS systems and workflows.

Shapefiles’ limitations

On the other hand, shapefiles come with its own set of limitations. There has been a fear that shapefiles run the risk to become more and more obsolete as the time goes by. This tendency became more obvious after the end of the 2000s. It was the time when it took of the smartphone revolution, the widespread use of mobile mapping applications, and the ever-increasing size of geographic data. The most critical disadvantages of the shapefiles according to our point of view are four.

In the first place, a shapefile is not able to handle very complex geometries and as a result you have to consider whether a shapefile would be handy for developing a more advanced and intricate GIS application.

Secondly, shapefiles are not code friendly and thus cannot be combined and deployed along with other front-end technologies in order to produce web maps or digital GIS applications based on a web browser client.

Thirdly, a shapefile cannot have more than 2GB insights for any of its component files, this limit translates to a maximum of roughly 70 million point features. In today’s world of big data, it is not a lot.

Lastly, as we showed earlier, a shapefile cannot be used as a standalone file as it typically comes with many other file formats together in order to constitute a functional geospatial dataset. Here there is a risk involved for the representation of a geo-dataset in case of improper management or in case of corruption or loss in one the constituted files.

The alternatives

In order the above drawbacks of the shapefile to be addressed, the experts, the industry and the GIS community have come up with new file formats in order to deal with the new challenges.

GeoJSON is a lightweight, web-friendly format used for sharing geographic data online and it is compatible with GIS tools like ArcGis and QGIS. It is based on JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) file and started becoming widely used in GIS after 2010. GeoJSON as its name suggests is a code-friendly file format and can be integrated and coded upon with digital and web maps which are based on real-time data exchange thanks to its affinity with JavaScript. It is capable of handling complex geometries and large data source, however, it can be slower in very large data, due to its textbase nature. Furthermore due to the fact that GeoJSON typically uses the WGS84 coordinate system, it might face limitations in local and regional GIS analysis which may require different spatial references.

GeoParquet is an up and coming format that is being developed to deal with very large spatial datasets that we often see today. GeoParquet is an encoding in Apache Parquet, a popular storage format for large tabular datasets. It defines how to store geometries in Parquet format. GeoParquet 1.0 was just released in September of 2023, and we can expect to see a lot more development in the coming years.

GeoPackage (GPKG) is an open, SQLite-based geospatial data format developed by the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) in 2014. GPKG is revolutionary in the sense that it is designed to store both vector (points, lines, polygons) and raster (imagery, elevation) data in a single, portable file (.gpkg). Unlike shapefiles, which require multiple files for different components, GeoPackage consolidates all data into a single, efficient database format. It is superior in terms of speed, file management and capacity to perform high level GIS analysis based on multiple criteria. GPKG after its first decade seems to consolidate itself as a standard for the GIS industry.

Table : GeoPackage VS GeoJSON vs Shapefile

Conclusion

After more than 30 years in the GIS world, shapefiles demonstrate still their resilience as a robust and trustworthy technology to make sense of geography, represent geographic features or trends and assisting the geographers in decision making. Shapefiles due to its small size have the ability to depict a large set of spatial data which have been collected and analysed in legacy / no code GIS systems over the course of 3 decades. Thus .shp format will remain topical for many professionals and especially for students and practitioners who aspire to become GIS experts in the future. However, to advance in the field of Geo-sciences, it is crucial to recognize the limitations of shapefiles and understand how the industry has addressed these challenges through the development of new file formats, GIS tools, and techniques.